A circular walk in the spectacular Yorkshire Dales

The small market town of Settle nestles in the beautiful North Yorkshire countryside. Follow the story of Settle’s development by exploring the town and its surroundings.

Begin by climbing to the Craven Fault to a former coral reef and a cave used by prehistoric animals. Discover how the stone walls that cover the hillsides reveal centuries of different farming methods.

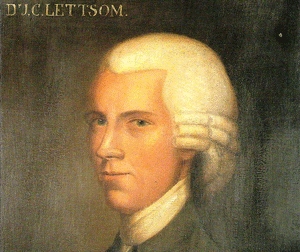

Then explore the medieval town and its oldest buildings. Find out how yeoman farmers became wealthy and how the Quakers gained commercial control of Settle.

This walk by local historian Tony Stephens was a Highly Commended entry in a competition to create a walk, organised by the RGS-IBG in collaboration with the University of the Third Age.